The cyberpunk genre is perhaps now more popular and relevant than ever, and the same can be said for actor Keanu Reeves. Together they would prove to be a powerful pairing with the sci-fi masterpiece The Matrix and the recent hit videogame Cyberpunk 2077.

However, that was not the case in 1995, when Johnny Mnemonic was released to confounded and indifferent audiences. How did the combined efforts of a newly minted A-list star, a noted visionary artist, and a pioneer in cyberpunk fiction result in a target of ridicule and a box office disappointment?

Jack in and fill your head with WTF Happened to this Movie!

The cyberpunk subgenre of science fiction can be broadly characterized with the theme of “high tech and low life” and it typically involves futuristic dystopian societies, advanced science and technology, body enhancements, dominant corporations, and sharp class disparity. Its origins and influences can be traced back to the works of authors like Harlan Ellison, Michael Moorcock and J.G. Ballard, and of course Philip K. Dick, whose stories have been adapted into movies like Total Recall, Minority Report, and what many see as the quintessential cyberpunk movie, Blade Runner.

But William Gibson is probably the name most commonly associated with cyberpunk. Gibson is credited with coining the term “cyberspace” long before the world was connected through fiber-optic and wireless networks, and his award-winning 1984 novel Neuromancer is considered a defining example of the genre, inspiring a generation of writers and artists.

That included provocative New York artist Robert Longo, who gravitated to Gibson’s groundbreaking vision of tech obsession, neon facade and criminal underbelly. Longo personally reached out to the writer, only to discover Gibson was also familiar with his work, and the mutual appreciation quickly evolved into friendship.

Longo had directed music videos for bands like New Order, REM and Megadeth, and made a short film called “Arena Brains” featuring Ray Liotta, Eric Bogosian and Steve Buscemi, and he was eager to shift into directing feature-length films. The Arena Brains producer was willing to finance a feature for under $2 million, and Longo decided on adapting Gibson’s early short story Johnny Mnemonic, with the author handing Longo the film rights in exchange for an original drawing.

Longo’s initial plan for Johnny Mnemonic was an avant garde black-and-white film noir with the vibe of material like Jean Luc Godard’s Alphaville and the Orson Welles classic Touch of Evil, but by 1990 that version of the project had collapsed. In the subsequent search for alternate funding, Longo and Gibson swiftly discovered that film companies didn’t have much interest in trivial productions for $1.5 million, but only larger budgets of at least ten times that figure.

Around that time, Longo had also entered the orbit of super-producer Joel Silver, who learned of the artist’s directing desires. Silver was interested in producing Johnny Mnemonic, and got the project set up with independent studio Carolco Pictures, and Longo was given a sort of audition by directing an episode of the Silver-produced HBO anthology series “Tales from the Crypt.” Carolco hired William Gibson himself to perform rewrites for what was then anticipated to be a $15 million production.

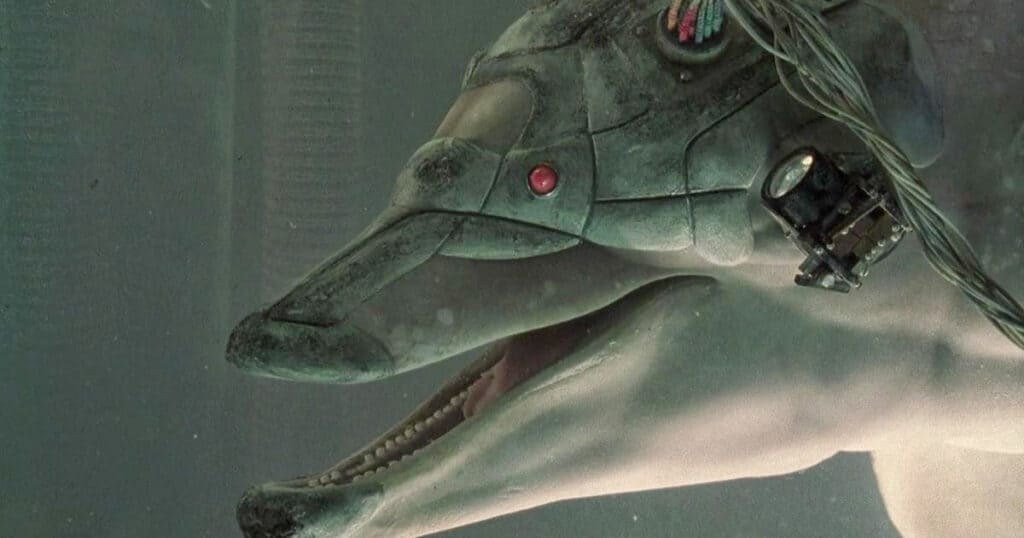

One of the early challenges had been expanding Gibson’s original 1981 story, which was a mere 22 pages, to a satisfying feature film length. The story’s broad strokes would remain – a courier carrying crucial encrypted data in a cranial hard drive, a double-crossing handler, a monowire-twirling Yakuza assassin, a cyborg dolphin, an outcast group called Lo-Teks.

To stretch the story, Gibson borrowed liberally from his own work like VIRTUAL LIGHT and introduced new plot points and “cinematic pacing”, with the data in Johnny’s overloaded brain storage now both a proverbial ticking time bomb and the invaluable cure to a global pandemic called Nerve Attenuation Syndrome. This mysterious disease, also known as the “black shakes”, is a result of constant exposure to the omnipresent technology that has become the world’s addiction. PharmaKom, the corporate owner of the sensitive data wants it returned so they can maximize profits, and they dispatch assassins to literally collect Johnny’s head.

There was one story complication arising from Gibson’s own prominence, however. The film rights to Neuromancer were already held by another studio, which meant the shared character of capable razor-fingered mercenary Molly Millions was off-limits for his own adaptation of Johnny Mnemonic. In her place would be a desperate bodyguard wannabe named Jane, who suffers from the “black shakes”.

But the movie would linger in development hell under Carolco, until the company ultimately imploded for a number of reasons, not the least of which was the notorious flop Cutthroat Island. One former Carolco executive still wanted to make Johnny Mnemonic and pitched it to various studios, but to no avail. The project would eventually find support through Canadian company Alliance… and around 20 different international financiers. Sony’s Tristar Pictures entered the mix and would distribute the movie in America, and the studio would invariably make creative demands and revisions that proved maddening for the writer and director.

The filmmakers secured Val Kilmer to play the lead role, but the involvement of certain foreign investors also came with casting conditions for overseas market appeal. German actor Udo Kier was cast as Johnny’s duplicitous handler Ralfi. Japanese superstar “Beat” Takeshi Kitano would play the corporate Yakuza kingpin, even getting additional scenes specific to the movie’s release in Japan.

But the backers’ insistence on including action star Dolph Lundgren left Longo and Gibson bewildered on exactly how to utilize the hulking Swede. Ultimately they took the script’s minor character of Karl the Street Preacher and reinvented him from heavy-metal biker into an imposing cyborg Christ figure with rambling diatribes and a crucifix knife.

Hardcore punk rock frontman Henry Rollins, who admitted he had no interest in science fiction but was a fan of Longo’s art, joined as flesh mechanic Spider. Filling out the main cast would be rapper Ice-T as anarchist leader J-Bone, and Dina Meyer, then mainly known for appearances on Beverly Hills 90210, making her feature debut as unstable enforcer Jane.

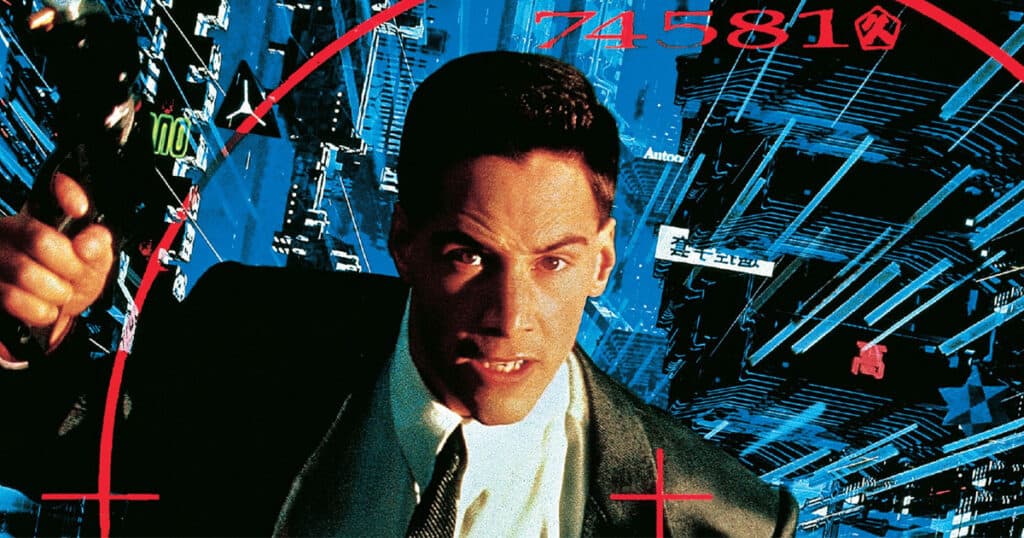

But before production started, Val Kilmer vacated the lead role over the obligatory “creative differences”. As Longo said, “Val wanted to make a different movie than I did, plus I think he might’ve had Batman cooking on the back burner.” Longo and Gibson were interested in Keanu Reeves, and scored the actor for a relative bargain price of $2 million, but his participation would have an even bigger financial and logistical impact. Because Reeves and Gibson were Canadian, the decision was then made to shoot in Toronto to take advantage of tax incentives. At the time, Johnny Mnemonic was the most expensive movie project in Canadian history with a $26 million budget.

For Longo, that location meant further compromise, because to qualify for the tax breaks it required a certain percentage of cast and crew also had to be Canadian. Longo could no longer use his intended director of photography Michael Chapman, whose credits included The Lost Boys, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull. Instead he would have to select from a very limited list of available Canadian cinematographers, ending up with a DP whose biggest credit was Weekend at Bernie’s.

So with the entire production process expected to last several months, Longo relocated to Toronto with his two kids and his pregnant wife, actor Barbara Sukowa, who would also play an important A.I. character in the film, and who would give birth to their son just before principal photography began, piling even more stress on the first-time feature director. Longo would also be working in what Gibson described as the most bitter, nightmarish winter in Canadian history.

The first scene shot was the opening street sequence, which found Longo wrangling dozens of extras in subzero temperatures, and he was immediately apprehensive about what he got himself into. He was operating on instinct and described directing as “like riding a bike without handlebars.” While he could envision how the film and characters should look, he was uncomfortable giving instruction to experienced actors. Reeves intentionally portrayed Johnny as robotic and inscrutable, but he also trusted Longo and supported him. Longo later discovered that shortly after filming had started, the producers seriously considered firing him and had actually promised the job to second unit director and stunt coordinator Vic Armstrong.

One area where Longo was confident was art direction. He wanted to highlight what he called “casual technology” and described his vision as “BLADE RUNNER if directed by Fellini”. Production designer Nilo Rodis, who had worked on Poltergeist and Empire Strikes Back, closely collaborated with Longo to bring his concepts and sketches into reality. Together they had to fabricate future Newark New Jersey and Beijing China, but the movie’s showpiece was Heaven, the enormous headquarters of the Lo-Tek guerillas and their cyborg dolphin colleague. The gigantic construction, suspended 15 feet above the floor of a Toronto warehouse, cost over $3.5 million alone. Gibson said the first time he stepped on the massive set and witnessed his imagination made real, he was rendered speechless for hours.

Because Longo and Gibson were both making their feature debut, they were viewed as unpredictable by the producers and financiers. As Longo put it, “Going from the art world to Hollywood is like trying to transfer to a college that doesn’t accept your credits.” Their creative control was continually challenged, and the script was constantly a point of contention even as cameras rolled. Longo wrestled with executives and his own DP over artistic choices, everything from the early overhead bathroom scene to the Gone with the Wind-style crane shot of Spider’s NAS trauma center. Even for something as seemingly innocuous as a tilted angle, the director would have to adjust the camera himself during lunch and immediately call action after break ended before it could be changed back. The studio suits had insisted on a final Terminator-style resurrection of Lundgren’s crispy cyborg, but Longo refused and instead shot a gag that somehow appeased the executives. [J-Bone: “Just garbage. Get that outta here!”]

The creative struggle of battling clichés in what Longo called “making art by committee” was compounded by juggling the frantic filming schedule with the exhaustion of new fatherhood, and the overwhelming pressures of being ultimately held responsible for all aspects of the production. Johnny’s tirade under the Lo-Tek bridge was even born of Longo’s ongoing frustrations. [“I want room service! I want the club sandwich! The cold Mexican beer!”] The rant was a late addition that Gibson wrote the night before at the request of the director, who felt the protagonist should be similarly agitated by his predicament, and it resulted in one of the movie’s most memorable scenes.

During production, Longo had also taken to stress eating, and gained over 30 pounds. But the leading man went in the opposite direction. As the movie was mostly shot in order, Reeves began severely limiting his calorie intake so Johnny would appear physically ill over the course of the movie from the data corruption in his head. A reshoot done later to add a new opening scene [Johnny shirtless in the hotel bed] proved fortuitous as the actor had returned to a healthy physique, further highlighting the contrast to Johnny’s final slender frame.

Getting through principal photography was not nearly the end of the agony for Longo and Gibson. As Johnny Mnemonic had barely entered post-production, Keanu Reeves suddenly became a major movie star when Speed hit theaters and reached blockbuster status with breathtaking velocity. With Reeves instantly catapulted onto the A-list, Tristar thought they had another potential blockbuster on their hands.

The studio had dollar signs in their eyes, and they also had a hole in their schedule. Production on their big planned summer release, the Julia Roberts Jekyll-and-Hyde thriller Mary Reilly, was a complete disaster and needed to be delayed. Johnny Mnemonic had originally been set as a smaller February release but would instead be shifted to the higher-profile and potentially lucrative Memorial Day weekend.

Even after all the previous creative concessions Gibson and Longo had made, the material they wrote and filmed was about to change dramatically as the studio took control of the edit. The versions that had been done by David Cronenberg’s longtime editor Ron Sanders were dragged to the recycle bin. The studio wanted less dialogue and more stunts, and slashed around 30 minutes of narrative cohesion to accelerate the tempo. The edges were filed off Reeves’ nihilistic character in an attempt to make him more likeable. Gibson’s trademark slang and cyberpunk elements were trimmed or simplified with looped in expository dialogue to reach a broader audience that one executive described as “the Gibson-impaired.” Much of Lundgren’s unhinged preacher, including his bombastic sermon about posthumanity, was cut by the studio for fear of offending the religious right. The finished score by Mychael Danna, which survived on the Japanese release, was replaced with all new synth-style music by The Terminator composer Brad Fiedel. Executives even considered changing the movie’s title to something basic like Johnny Gets His Gun.

The studio was determined to have a hit. On top of all the additional costs for their alterations, including computer sequences done by Sony’s digital effects division, the movie’s marketing was propelled by the power of Sony’s hype machine. Millions more dollars were sunk into a tie-in CD-ROM game with full-motion video featuring actors who were distinctly not the original movie’s stars. Attempting to capitalize on the explosive growth of the world wide web, the company’s new technology division established a promotional online scavenger hunt for cash and prizes. The typically reclusive William Gibson was persuaded to engage in awkward online Q&A sessions with fans. Executives simplistically assumed the Internet would provide “turbo-charged word of mouth.” And Speed’s now-bankable hero Keanu Reeves was at center of the movie’s advertising.

Ultimately none of it mattered. Johnny Mnemonic was released in North American theaters on May 26, 1995. Positioned against new releases Casper and Braveheart along with holdovers Die Hard with a Vengeance and Crimson Tide, Johnny didn’t stand much of a chance, opening in sixth place with $7.4 million and ending with a domestic total of $19 million. While moviegoers were left perplexed or impartial, critics were about as kind as Dolph’s brutal hitman, calling the movie “high-tech trash”, “derivative”, “shabby”, and perhaps expectedly, “Johnny Moronic.”

To say the creators were disappointed with the final result would be a colossal understatement. Gibson called the theatrical version “a really extreme example of not being the director’s cut.” He describes their original vision as “an ironic fable of the information age” that was also intended as “a broadly comic homage to all the good bits in bad science-fiction movies.” He said, “The film that was released bears almost no resemblance to the film we shot. Imagine David Lynch’s Blue Velvet recut by the distributor in an attempt to make a more accessible, mainstream film.”

Gibson even published his original screenplay because he wanted to explicitly demonstrate the differences between what he and Longo wrote and filmed, and what the studio actually released.

Longo simply described the studio decision-makers as “complete idiots” and called the entire process “torturous,” along with other adjectives like unsettling, corrupt and devastating. Unsurprisingly, he has not directed another feature since, and claimed the experience gave him PTSD that caused creative and financial difficulties in returning to the art world he had temporarily departed.

Despite all that, Longo described his collaboration with Gibson and Reeves as “very rich” and they still remain friends, recently reuniting virtually to discuss Longo’s black-and-white update of the movie. Yes, even after all the trauma, Longo decided to revisit Johnny Mnemonic 25 years later, first ripping a Blu-Ray copy and converting it to black-and-white as he initially envisioned. Eventually Sony provided high-resolution footage for Longo and a colorist to professionally grade into black-and-white, followed by festival screenings in 2021 and a release on Blu-Ray and iTunes (it’s also streaming on the Criterion Channel).

While Longo still says the movie itself is only about 60% of what he originally wanted, the black-and-white version serves as a redemption of the aesthetic he aimed for in the beginning: a scrappy $1 million art film with grunge and attitude, and computer graphics that look intentionally stylized rather than dated. He has no plans to revisit the movie further, so while the extended Japanese cut can be found on various foreign DVD releases, a legitimate director’s cut of Johnny Mnemonic will likely remain a cyber fantasy.

William Gibson’s influence can still be found in countless movies and shows, but besides Johnny Mnemonic, only his stories New Rose Hotel and The Peripheral have actually been adapted, leaving the iconic NEUROMANCER as yet unrealized in live-action.

According to the filmmakers, Johnny Mnemonic did eventually turn a profit thanks to international and home video releases, but the common perception is that the movie was a bomb and something of a punchline. But is that justified? More a victim of obvious creative interference than its own ambitions, the movie has certainly developed a cult following over the years, and in many ways was eerily prescient, taking place in the year 2021 during the middle of a global pandemic. Sure, the “futuristic” 320 gigabyte storage capacity now seems quaint, but technology obsession, data significance, class disparity, information warfare and profiteering megacorporations are very much part of modern life.

1995 was a big year for movies with elements of cyberpunk and dangerous tech [The Net, Hackers, Virtuosity, Strange Days, Judge Dredd and Ghost in the Shell (anime)] , but few had the compelling world-building, oddball cast, creative pedigree and longevity of Johnny Mnemonic.

Originally published at https://www.joblo.com/wtf-happened-to-johnny-mnemonic/